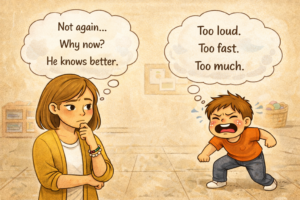

Who is this really challenging?

In room meetings, I often hear the words — usually between discussions about interests and upcoming events —

“We need to talk about a challenging behaviour.”

And almost every time, my first thought is:

What challenging behaviour?

Not because nothing happened.

But because I find myself wondering —

Who is this really challenging?

Maybe I don’t see the behaviour as challenging. Why?

Over the years, I’ve stayed curious. I’ve asked questions. I’ve tried to look beneath so-called “challenging behaviours.” And somewhere along the way, I stopped looking at the behaviour and started seeing the child beneath it.

We have to ask ourselves: to whom is this behaviour challenging?

For a child, behaviour is often communication — the best tool they have in the moment when they don’t yet have the words, the skills, or the regulation.

Yes, some children quickly learn which behaviours get a reaction. But even then, I wonder: is that “challenging”… or is it information? If a behaviour reliably gets a result, it makes perfect sense that a child would repeat it. (Honestly, most adults do the same thing.)

And if we keep saying, “They’re not listening,” or “They’re being challenging,” can we blame children for using the tools they have — especially if we haven’t taken the time to understand what’s driving it, and what skill is missing?

Another question arises: challenging compared to what expectation?

We set the expectations. But are they developmentally appropriate for this child, in this moment, in this environment?

When I say in this moment, I mean exactly that.

Development isn’t straightforward. Regulation isn’t consistent. Capacity isn’t fixed.

A child who transitioned smoothly yesterday might crumble today. A child who sat beautifully at circle time in the morning may not have the same strength left in the afternoon. And yet, I often see us hold the expectation steady — as if children should meet it the same way, every time, regardless of what their nervous system is carrying in that moment.

We adjust expectations for ourselves all the time. If we’re tired, overwhelmed, or distracted, we know our patience and focus shift. We might need an extra coffee. Or three.

But children are expected to regulate, transition, share, and comply consistently — while their brains are still wiring those very skills.

So the question becomes:

Is the behaviour challenging — or is the expectation misaligned with the child’s capacity in that moment?

We can’t hold every child to the same expectation in the same way. We have to meet children where they are before we can ask them to move forward.

And then the hardest question:

Is it challenging because it disrupts learning — or because it disrupts our plan?

Does it feel bigger because we’re in the middle of a rushed transition? Because we need to finish the activity before lunch? Because our own nervous system is already stretched thin?

Or is the behaviour truly affecting the child’s ability to engage, connect, and enjoy learning through play?

The Mindful Moment

I see this most clearly during our daily Peace of Mind sessions.

We sit together for a mindful moment. Back straight. Legs crossed. Eyes closed — if we choose. We breathe slowly. We practice stillness.

And then there are the movers.

The ones who crawl quietly across the carpet.

The ones who slide on their knees.

The ones who invent entirely new yoga poses I have never seen before.

And if I’m honest, there are still moments when I redirect them.

Sometimes it’s because they drift into someone else’s space. Sometimes they begin whispering mid-breath. But sometimes — if I’m being really honest — it’s because their movement disrupts me.

It interrupts the calm I am trying to create. It pulls at the structure I carefully planned.

And there have been days when I paused a beautifully flowing session to address the movement… only to realize later that I was the one who disrupted the moment.

Because what if that child’s body needed to move in order to regulate?

What if stillness isn’t the only form of mindfulness?

I’ve had to remind myself that breathing can happen while knees are sliding across the carpet. Regulation can happen with eyes open. Learning can happen in motion.

Now, when possible, I create space instead of correction. I let movement coexist with stillness — unless it truly disrupts someone else’s ability to engage.

And more often than not, when I adjust, the moment settles on its own.

Somewhere along the way, we began treating behaviour as a child’s problem to fix — rather than a signal for us to understand.

If we look at the formal definition, challenging behaviour is described as repeated patterns that interfere with learning or social interaction (Dunlap et al., 2022).

But here’s what I struggle with: in weekly meetings, the behaviours being discussed are often isolated moments. Not patterns. Not chronic disruption. Just hard moments.

And in those moments, we interpret what we see — but we rarely see the whole story.

We see the push.

We don’t see the exhaustion.

We see the running.

We don’t see the anxiety.

We see the “noncompliance.”

We don’t see the missing regulation skills.

We see the behaviour.

We don’t always see the need underneath it.

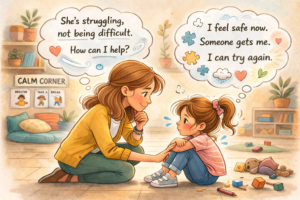

And if that’s true — if behaviour is communication, if expectations must be responsive, if our lens shapes the story — then the work shifts.

It stops being about fixing the child.

And starts being about adjusting ourselves.

Not lowering expectations.

But aligning them.

Not excusing behaviour.

But understanding what skill is missing.

Not reacting in the moment.

But preparing for the next one.

Reimagining behaviour doesn’t mean ignoring it. It means slowing down long enough to ask better questions.

Before labeling a moment as “challenging,” I now ask myself:

- Are this child’s basic needs met? (Hungry? Thirsty? Overstimulated?)

- Is this connection-seeking rather than attention-seeking?

- Is this a regulation skill they haven’t developed yet?

- Are my expectations clear — and developmentally appropriate?

- Is this behaviour reactive to something else in the environment?

Because once we identify the need, the strategy changes.

When a child struggles with transitions, we don’t punish the meltdown — we prepare the nervous system. We give warnings. We offer choices. We stay close.

When a child pushes, we don’t label aggression — we teach regulation and model language.

When a child “doesn’t listen,” we ask whether trust has been built first.

Maybe the real question isn’t,

“How do we manage challenging behaviour?”

Maybe it’s this:

Who is this really challenging?

Because sometimes the hardest part isn’t the child’s behaviour.

It’s adjusting our lens, our expectations, and our response.

And when we change that —

the behaviour often changes with us.

Behind the crayons, the coffee gets cold, the plans shift, and the real learning often starts with us.

If you’re walking this journey too — educators, parents, caregivers — I’d love for you to join me. You can subscribe below and receive reflections straight to your inbox.

— The Teacher Behind the Crayons

References

Dunlap, G., Lee, J. K., & Ahn, S. (2022). Understanding Challenging Behavior: The Path to Behavior Support (By U.S. Department of Education). https://challengingbehavior.org/docs/2022-05-18-WTF-Understanding-Challeging-Behavior-Handouts.pdf

Discover more from Behind The Crayons

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

You May Also Like

I See You – A Story About Slowing Down and Looking Closer

June 25, 2025

Emotional Intelligence: Teaching children about Self- Awareness

June 20, 2025