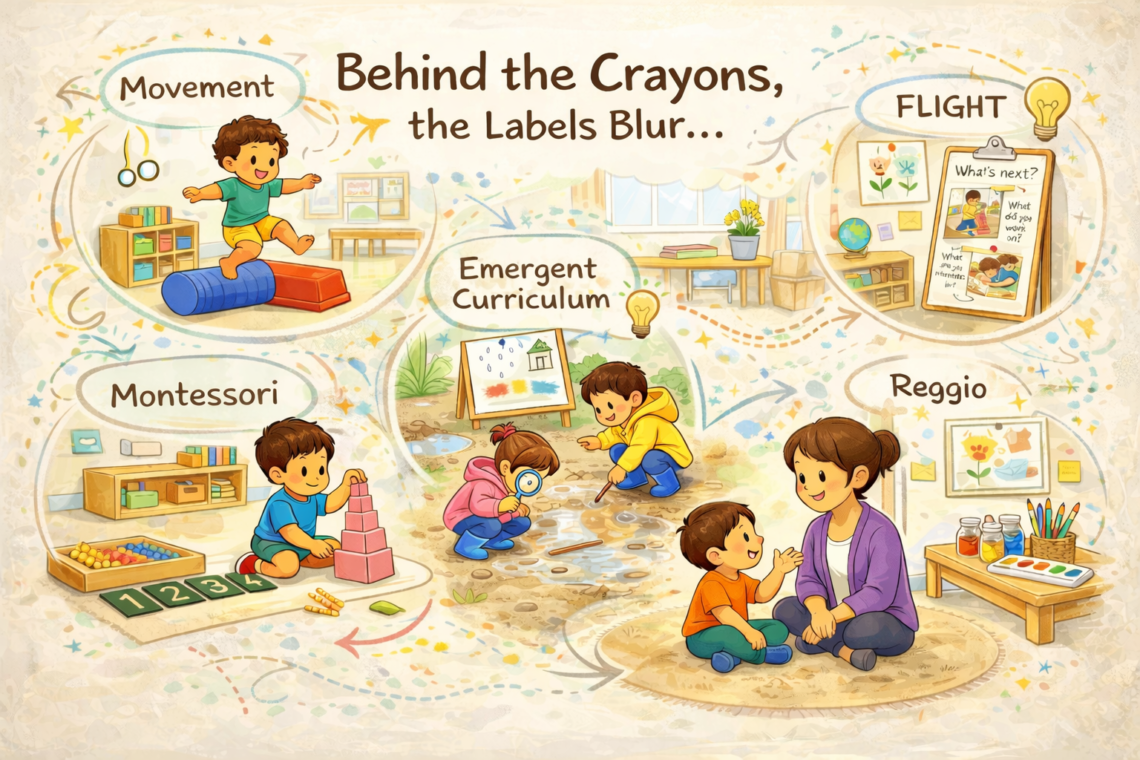

Behind The Crayons the Labels Blur…

In early childhood education, curriculum often sounds like a choice you’re supposed to make once—pick an approach, commit fully, and never look back. Montessori or Reggio. Emergent or structured. Play-based or outcomes-driven. As if learning fits neatly into one box, one philosophy, one laminated poster on the wall.

But classrooms are rarely that tidy.

Children arrive with different needs, temperaments, histories, and ways of making sense of the world. Some crave order and repetition. Others need movement, noise, and connection. Some learn best alone, deeply focused. Others learn in the middle of shared chaos, dramatic play, and loud negotiation over whose turn it is to be the baby.

Over the years, I’ve had the opportunity to experience five different approaches to early learning: Montessori, Reggio Emilia, Emergent Curriculum, movement-based learning, and the FLIGHT framework. I didn’t move through these philosophies as a checklist or career plan. I met them in real classrooms—with real children, real restrictions, and very real moments of wondering whether what I was doing was actually helping.

Each approach offered something valuable. Each one also revealed its limits. Some asked me to step back. Others asked me to lean in. Some gave children space. Others reminded me how much relationships matter. And FLIGHT—quietly, persistently—wove itself through all of them, offering a way to reflect rather than prescribe.

This isn’t a post about choosing the best curriculum.

It’s about what happens when theory meets tiny chairs, big emotions, limited time, and children who don’t read the philosophy before walking into the room. It’s about what these approaches look like in practice—when they work, when they don’t, and what they taught me along the way.

Because behind the crayons, the labels blur.

What remains are children, educators, and the relationships that carry learning far beyond any framework.

Montessori: When the Philosophy Meets the Classroom

When I was first introduced to Montessori, I loved it.

The philosophy felt respectful and hopeful—children as capable, curious learners who could direct their own learning through hands-on experiences. Independence was celebrated. Choice mattered. Children were trusted to work at their own pace, following their interests rather than racing an invisible clock.

On paper, it felt like a dream.

A calm, orderly dream.

A dream where no one spills water on purpose.

And in some classrooms, it really was.

But over time—and across different settings—my relationship with Montessori became more complicated.

One of the challenges with Montessori is that the term itself isn’t trademarked. This means many centres proudly adopt the label without fully committing to (or fully understanding) the philosophy behind it. As a result, “Montessori” can mean anything from thoughtfully child-led learning… to very small chairs and very big expectations.

I experienced this contrast firsthand.

In one environment, Montessori principles were gently woven into play. Materials were thoughtfully introduced, independence was encouraged without pressure, and children moved freely between focused individual work and shared moments of connection. It felt calm, respectful, and responsive—like the philosophy was alive and breathing, not laminated and taped to the wall.

In another setting, the experience was night and day.

The same label was used, but the practice felt rigid and overly controlled. Choice was limited. Materials were closely guarded (sometimes like museum artifacts). The classroom was quiet—but not peaceful. Independence looked suspiciously like compliance, and learning felt heavily teacher-led despite the philosophy stating otherwise.

This is where some of the common critiques of Montessori start to make sense.

Montessori is often described as too structured, too quiet, or too individualistic. And there’s an argument—one I tend to agree with—that an overemphasis on individual work can limit opportunities for social interaction, collaboration, and imaginative group play. Some children thrive in shared chaos, negotiation, and dramatic play that involves seventeen roles and absolutely no clear plot.

For those children, a strictly individual-focused environment can feel less like freedom and more like being told to sit with your thoughts… and your bead chain.

And yet—when Montessori is held with intention and flexibility—it tells a very different story.

At its heart, Montessori is rooted in trust. Trusting children to be capable. Trusting them to try, to repeat, to spill, to clean it up, and to try again. In a thoughtfully prepared environment, children explore hands-on materials, make meaningful choices, and work at their own pace—often with a level of concentration that makes adults freeze mid-step and think, I should not breathe right now.

The educator’s role shifts dramatically. You observe more than you speak. You guide gently instead of stepping in immediately. You resist the very human urge to “just fix it real quick,” even when watching a task take approximately three business days.

But here’s the part that matters most—and gets talked about the least.

How Montessori looks in practice depends entirely on the people implementing it. Educator experience, training, cultural background, expectations, and access to resources all shape the outcome. Two classrooms can follow the same philosophy and create completely different experiences for children—both proudly labeled Montessori.

What I’ve come to understand is that Montessori itself is not the problem or the solution.

It’s a tool.

And like any tool, it works best when used with skill, reflection, and a willingness to adapt—rather than strict rules and a silent stopwatch.

When applied thoughtfully, Montessori can nurture independence, confidence, and deep respect for children as learners. When applied rigidly, without flexibility or reflection, it can lose its warmth—and its joy.

Reggio Emilia: Beautiful in Theory, Demanding in Practice

Reggio Emilia often arrives wrapped in beautiful language.

Children as capable.

Children as thinkers.

Children as co-constructors of knowledge.

The philosophy centres on child-led learning, where children’s interests and experiences are not just noticed, but deeply valued. Relationships matter. Community matters. The environment itself is considered the “third teacher,” quietly shaping learning through light, materials, and invitation.

When I first experienced Reggio Emilia in action, I was inspired.

The classroom didn’t feel static—it felt alive. Experiences were thoughtfully tailored around what children were genuinely curious about, and you could see those curiosities reflected everywhere: in loose parts, in open-ended provocations, in displays that changed almost as often as children’s questions. Learning didn’t disappear at the end of the day; it lived on the walls through documentation, making thinking visible in a way that felt respectful rather than performative.

It was beautiful.

And also… a lot.

Because Reggio Emilia, when implemented authentically, asks a great deal of educators.

This approach is often praised for being flexible, creative, and deeply responsive—but that same openness can be challenging. Some children thrive with clear structure, routine, and predictability, and the open-ended nature of Reggio can feel overwhelming without strong scaffolding. Not every child wants a blank canvas every day. Some would really prefer instructions. Or at least a starting point.

And then there’s the reality behind the documentation.

Documentation is a cornerstone of Reggio practice—observing, recording, reflecting, revisiting, and extending children’s learning. Done well, it deepens understanding and honours children’s thinking. Done poorly (or rushed), it becomes something created after hours, fueled by cold coffee and guilt, rather than meaningful reflection.

Reggio Emilia demands time.

Time to observe without interrupting.

Time to reflect without rushing.

Time to document without turning it into a performance.

When educators aren’t given that time—and often, they aren’t—the philosophy becomes incredibly difficult to implement authentically. What was meant to be child-led can quickly become adult-curated. What was meant to honour thinking can turn into beautifully displayed moments that look impressive but feel disconnected from the actual learning.

And yet, when the conditions are right, Reggio Emilia is powerful.

It invites educators to listen deeply, to take children’s ideas seriously, and to see learning as something constructed together. It reminds us that children don’t need us to hand them answers—they need us to sit beside them while they figure things out, even when the process is messy, nonlinear, and occasionally involves glue where glue was never meant to be.

What Reggio has taught me is this: child-led does not mean child-left-alone. It requires skilled educators who can balance freedom with intention, curiosity with care, and creativity with responsibility.

Movement Matters: When Learning Lives in the Body

At one point in my career, I worked in a classroom focused primarily on physical education.

Not all day, of course—I wasn’t running a tiny boot camp. The room operated with two groups daily, one in the morning and one in the afternoon, with nap time in between. Children rotated between three different environments across the day, based on their developmental needs, schedules, and what made the most sense on paper.

On paper, it was impressive.

And in many ways, it worked.

Physical movement is critical in early childhood. It supports not just physical development, but cognitive, emotional, and even language growth. In this space, movement wasn’t an “extra” or a reward—it was the curriculum. We intentionally targeted locomotor skills, stability, object manipulation, health and wellness, and early gymnastics. Each week (or sometimes every other week), we introduced a new theme through games, challenges, and playful learning.

Children climbed, jumped, balanced, threw, rolled, ran, and discovered what their bodies could do. Confidence grew alongside coordination. Frustration showed up—and was worked through—right there on the mats and floors. There was joy. There was sweat. There were also a lot of shoes that somehow never ended up back on the right feet.

I loved the emphasis on physical development. Truly. Watching children realize they could do something their body couldn’t quite manage before was powerful. Movement gave some children a voice they didn’t yet have with words.

But there were challenges.

The constant transitions were hard on the children. Moving between multiple environments in a single day meant frequent goodbyes, shifting expectations, and resetting routines. For some children, that flexibility was exciting. For others, it was exhausting—especially for those who thrive on predictability and deep connection with familiar adults.

There was another challenge that lingered quietly beneath the surface.

Teachers didn’t always get to see the “whole child.”

Because children rotated between classrooms, each educator only held a piece of the picture. This sometimes led to differing opinions about what a child needed or what was “best,” based on limited interactions rather than a full understanding of the child’s day, emotions, and relationships.

And that’s where the biggest learning came for me.

What matters most isn’t the classroom a child is in.

It isn’t the focus of the curriculum.

It isn’t even how beautifully the program is designed.

It’s the relationships.

Children learn best when they feel known, safe, and connected. Movement can support learning in incredible ways—but without strong, consistent relationships, even the best-designed environments can fall short. A child may master a balance beam, but still need a trusted adult who understands their fears, frustrations, and triumphs beyond that moment.

This experience reminded me that no curriculum exists in isolation. Physical education, like every other approach, works best when it is woven into a broader understanding of the child—not separated from it.

Emergent Curriculum: Trusting the Questions (and Yourself)

The emergent curriculum is often described as being similar in spirit to Reggio Emilia—but broader in scope and a little less precious about how things are supposed to look.

At its core, emergent curriculum centres on following children’s interests to create meaningful learning opportunities. Those interests become the starting point for everything: math and literacy, dramatic play, practical life skills, outdoor exploration, sensory experiences, and art. Learning unfolds through play—not as an add-on, but as the main event.

From the outside, this can look chaotic.

“Where’s the plan?”

“How do you know what they’re learning?”

“Isn’t this just… free play?”

These are fair questions. Emergent curriculum is often criticized for being too loose, too unstructured, and too difficult to measure—especially for children who need routine, predictability, and clear expectations. Without strong educator intention, it can drift. It can feel reactive instead of responsive.

But when it works, it works beautifully.

Personally, emergent curriculum is where I felt myself grow the most as an educator.

This approach asked me to slow down and really watch. To listen more than I talked. To notice patterns in children’s play instead of rushing to redirect it. It pushed me to become more reflective, more intentional, and more confident in tailoring learning to what children were naturally curious about—rather than what I thought they should be interested in.

Planning didn’t disappear. It just changed.

Instead of planning weeks ahead, I planned in response. I observed, documented, reflected, and then intentionally extended learning. Math showed up in block towers and snack routines. Literacy lived in dramatic play signs, dictated stories, and shared conversations. Science snuck into puddles, shadows, and “why” questions that arrived just before lunch and refused to wait.

Emergent classrooms are often noisy. Ideas overlap. Negotiations happen loudly. Learning spills across areas and doesn’t always stay neatly contained. It requires educators to be comfortable with uncertainty—and to trust that meaningful learning doesn’t always follow a straight line.

And yes, flexibility can be challenging.

Some children need more predictability than emergent curriculum naturally offers, and that needs to be honoured. Emergent doesn’t mean absence of structure—it means flexible structure. Routines still exist. Expectations still matter. The difference is that the curriculum bends without breaking.

That flexibility, to me, is its greatest strength.

Emergent curriculum teaches children that their ideas matter. It teaches educators that learning doesn’t have to be perfectly planned to be deeply meaningful. And it reminds all of us that curiosity is worth following—even when it takes us somewhere unexpected.

FLIGHT: The Framework I Carry Into Every Classroom

FLIGHT isn’t a curriculum in the way Montessori or Reggio Emilia is.

It doesn’t come with specific materials, a prescribed setup, or a checklist of what learning should look like by Friday. Instead, FLIGHT is a curriculum framework designed to guide educators working with young children—from birth to before six—in both centre-based and home settings.

And honestly? That difference matters.

FLIGHT is flexible and evolving by design. It places children’s play at the centre of learning and asks educators to think deeply about how children learn, who they are learning with, and what messages we send through our environments, relationships, and choices.

When I took the FLIGHT course, it felt like something clicked.

Not in a dramatic, fireworks kind of way—more like the quiet relief of realizing, Oh. This already lives in me. The framework echoed everything I believed but hadn’t always had the language for: that children are mighty, capable learners. That education is shaped by attitude as much as intention. That relationships matter more than rigid outcomes. And that the journey—the messy, nonlinear, beautifully human part—matters far more than the destination.

What I appreciate most about FLIGHT is that it doesn’t ask educators to abandon the approaches they already use.

It asks us to look at them more thoughtfully.

FLIGHT can live alongside Montessori, Emergent Curriculum, Reggio Emilia, movement-based learning, or any other approach because it’s not about what you do—it’s about how and why you do it. It encourages reflection over certainty, curiosity over control, and connection over compliance.

In practice, FLIGHT shows up in questions rather than answers. It invites educators to pause and ask: Who is this child becoming? What experiences are shaping them? Whose voices are present here—and whose are missing? It challenges us to examine our own assumptions and to recognize that early childhood education is never neutral, even in moments that seem small.

And yes—this kind of reflection can feel uncomfortable.

FLIGHT doesn’t hand you a neat plan or a final destination. It encourages educators to support children in finding their destination, not the one we’ve quietly mapped out for them. That requires trust. It requires humility. And it requires being okay with not always knowing where the learning will lead.

Which, if we’re honest, is both freeing and mildly terrifying.

But FLIGHT also reminds us that learning happens in relationships. That children don’t need us to steer them constantly—they need us to walk alongside them, noticing, listening, and responding with care. It asks us to be present rather than perfect, reflective rather than rigid.

Working across these approaches has taught me that there is no perfect curriculum.

Montessori reminded me of the power of independence and deep concentration (and the patience required to watch someone pour water for what feels like an entire fiscal quarter). Reggio Emilia showed me what happens when we truly listen and make children’s thinking visible—while also discovering how much time thoughtful documentation actually takes. Emergent curriculum strengthened my ability to respond rather than control, and to trust that learning can grow from a puddle, a question, or an argument about whose turn it is to be the baby. Movement-based learning proved that development lives in the body as much as in the mind—and that sometimes the most important breakthroughs happen mid-cartwheel. And FLIGHT gave me the language—and the courage—to reflect on it all without needing a neat bow on top.

Each philosophy offers something valuable. Each one has limits. Some thrive on structure; others lean into flexibility. Some emphasize independence; others prioritize collaboration. Some are beautiful in theory but demanding in practice (especially on three hours of sleep and cold coffee). What truly shapes children’s experiences isn’t the name of the framework on the wall—it’s how thoughtfully, flexibly, and relationally it’s lived out in real moments with real children.

Because curriculum doesn’t teach children.

People do.

Behind the crayons, the philosophies blur. The carefully curated materials, the documentation panels, the rotating schedules, the beautifully written frameworks—they all fade into the background when a child needs comfort, encouragement, or someone to notice their small but mighty victory. What remains are children who want to be seen, educators who are learning alongside them, and relationships that carry learning far beyond any checklist.

In the end, it’s not about choosing the right approach.

It’s about showing up with intention.

Staying reflective when things don’t go as planned.

Being willing to adapt when the child in front of you needs something different than the philosophy suggests.

And remembering that education, like childhood itself, is not straight forward, not perfect, and certainly not one-size-fits-all.

It is relational.

It is responsive.

It is sometimes loud, occasionally messy, and almost always humbling.

And at its very best, it’s not about the curriculum at all — it’s about the small humans in front of us, and the big responsibility and privilege of growing alongside them.

Behind the crayons, the lesson plans change, the coffee gets cold, and the children keep teaching me. And honestly? I wouldn’t have it any other way.

— The Teacher Behind the Crayons

💬 I’d love to hear from you! Have you had a “pause and breathe” moment with your little learners? Or maybe a funny story about a fire drill and a glitter explosion? Share your thoughts, questions, or classroom wins in the comments below—let’s keep the conversation going.

References

Reggio Emilia- https://sightlines-initiative.com/images/Library/reggio/ReggioAug06_tcm4-393250.pdf

Emergent Curriculum- https://elc.utoronto.ca/about-us/emergent-curriculum/

Flight Framework- https://www.flightframework.ca/

Discover more from Behind The Crayons

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Peace of Mind Curriculum

You May Also Like

Emotional Intelligence: Teaching children about Self- Awareness

June 20, 2025

Emotional Intelligence: Teaching Children About Self-Regulation

June 23, 2025