Emotional Intelligence: Teaching children to Recognize and Label Their Emotions

Let’s face it—preschoolers feel everything, and they feel it big. One minute they’re laughing uncontrollably, the next they’re under a table because someone got the blue cup. It’s all part of learning to navigate the world of emotions—and that’s where emotional intelligence comes in.

In this and the next 5 posts, we’ll take a closer look at what emotional intelligence really means for young children: how it develops, why it matters, and how we, as educators and caregivers, can support it with intention, patience, and a good sense of humor. From self-awareness and self-regulation to empathy, motivation, and social skills, each post will break down the building blocks of emotional intelligence and offer real-life stories, strategies, and maybe a few relatable teacher moments too.

Because at the end of the day, helping children grow emotionally isn’t about having all the answers—it’s about showing up, staying curious, and offering just the right support at just the right time… one gentle nudge (and deep breath) at a time.

What does it mean to be emotionally aware?

Emotional intelligence (EI)—also called emotional awareness—is all about recognizing and understanding your own feelings and how they influence your thoughts and actions (Sutton & Millacci, 2021). Think of it as the inner compass that helps us manage ourselves and connect with others. Daniel Goleman (2005) outlines five key components of EI: self-awareness, self-regulation, motivation, empathy, and social skills. These aren’t just grown-up skills—they’re incredibly important for our little learners, too. You can explore each of these components and find practical, playful ways to help nurture them in young children throughout my other posts (because yes, each one deserves its own spotlight!).

Why is emotional intelligence important in preschool children?

Picture this: a child who can count to 100, write their name with flair, and name every letter of the alphabet—but when it’s time to share the blocks or deal with someone cutting in line, things go off the rails. They might struggle to join in play, feel overwhelmed by small injustices (“He looked at me funny!”), or have big reactions to both excitement and frustration. Of course, it’s wonderful when a child picks up academic skills early—but if they don’t also learn how to understand and manage their emotions, that academic sparkle can dim fast. Learning starts to feel like a chore instead of an adventure, and building relationships becomes scary instead of exciting. On the flip side, emotionally aware preschoolers have a solid foundation for lifelong success. They’re the ones who bounce back from challenges, form healthy friendships, and grow into resilient, emotionally healthy learners—not just ready for school, but ready for life.

For most of us adults, recognizing and understanding emotions is second nature—we’ve had years of practice (and maybe a few tearful car rides). But it’s easy to forget that children are just beginning to figure all of this out. Sometimes, without even realizing it, we expect them to handle emotions like little adults. We say things like, “Don’t be sad,” or “Stop crying, it’s not a big deal,” thinking we’re offering comfort. But to a child, these words can feel like their feelings don’t matter. When we dismiss their emotions, we unintentionally teach them to bottle things up instead of working through them. And let’s be honest—none of us are at our best when we’re emotionally stuffed full like an overpacked backpack. Helping children feel their feelings is the first step toward helping them manage them.

Where can we start to support our children in the moment and pave them a path to succeed in the future?

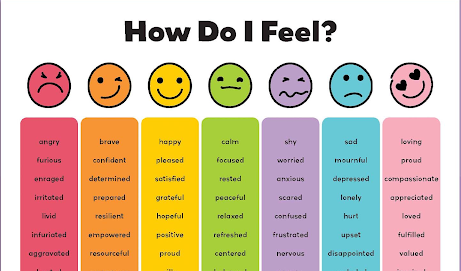

Teaching children to label their emotions is often the easiest entry point—it’s like the “hello” of emotional intelligence. But while identifying feelings like happy, sad, or mad is a great start, it’s really just the top layer of a much deeper journey into emotional understanding. Emotional awareness goes far beyond the basics, and the truth is, children are often capable of grasping far more complex feelings than we give them credit for (yes, even the three-year-old who just licked the play-dough can understand jealousy). In addition to the usual suspects—joy, sadness, anger, and fear—consider weaving in words like love, excitement, shyness, jealousy, confusion, frustration, anxiety, disappointment, compassion, embarrassment, calmness, boredom, and eagerness. There are many more, and the more we name them, the more children learn to navigate them. Try to connect these emotions to real moments in their day—“You look disappointed we can’t go outside,” or “That tower made you feel so proud.” These simple connections help emotions come alive in everyday life.

You’ll find some of my favorite ways to teach emotion labeling—and a few real-life classroom wins—just below.

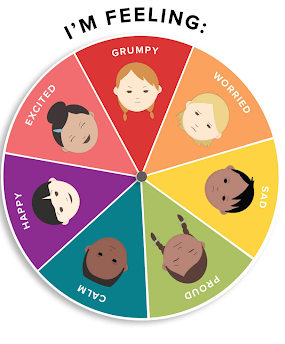

Using visual aids like emotion charts and wheels

Emotion wheels and charts are some of my go-to tools in the classroom. They help children move beyond the usual “happy” or “sad” labels and start exploring a richer emotional vocabulary—like “disappointed,” “overwhelmed,” or “frustrated” (Sutton & Millacci, 2021). These visuals offer a clear, accessible way for children to point to what they’re feeling, especially when the words feel too big or jumbled to say out loud. For little ones (or any child with cognitive or language difficulties), emotion charts take something as abstract as feelings and make it tangible. They lighten the cognitive load of trying to find the “right” words and instead let the focus stay on the actual emotional experience (Neff, n.d.). Honestly, sometimes I wish adults had an emotion wheel in the staff room—we could all use a little help decoding our moods before that second cup of coffee!

Experience:

One morning, a three-year-old in my care was clearly having a big feeling—but couldn’t quite tell me what it was. You know the look: furrowed brow, fidgety hands, that tiny storm cloud hanging just above their head.

So, I gently invited them over to our calm corner—home of cozy pillows, soft lighting, and the ever-handy Emotion Chart. It’s a simple visual with expressive faces showing all sorts of feelings: happy, sad, angry, shy, confused, frustrated, worried—you name it, it’s probably laminated.

The child studied the chart carefully. Eyes scanned the faces like a tiny emotional detective. After a moment, they pointed to “worried.”

I gently confirmed, “Worried?”

They nodded.

That little nod opened the door. I began offering gentle prompts—“Are you worried about something at school? About someone at home?” Bit by bit, we peeled the layers back until the child said:

“I’m worried my mommy and daddy won’t have time to play with me.”

When I asked why they thought that, the answer was heartbreakingly honest:

“Because my brother always has them.”

That’s when it all made sense. The child had a younger sibling—still in that high-needs baby phase—and clearly felt pushed to the side, even if unintentionally. I explained in simple terms how babies do need a lot of care, but it doesn’t mean parents love any less. Then I offered an idea: maybe we could talk to mommy and daddy about setting a special playtime just for them.

And just like that, with one small pointer finger and a well-used chart, we had translated an overwhelming emotion into a real conversation. A little support, a little empathy, and one very wise three-year-old reminded me (again) that sometimes kids do know what they feel—they just need the right tools to show us.

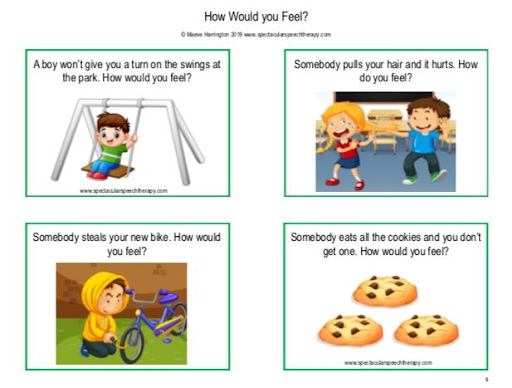

Engaging in role-playing scenarios

Emotional role play is one of those classroom gems that packs a big punch. Acting out different feelings through pretend scenarios not only supports social-emotional learning—it also sparks meaningful personal growth. It gives children a safe, playful space to explore tricky emotions like jealousy, frustration, or embarrassment without the heat of the real moment. Whether they’re pretending to be a sad dragon who lost their tail or a proud astronaut landing on the moon, role play builds self-awareness, empathy, and social skills all at once. It’s also a great way to sneak into those “big feelings” that kids might not be ready—or willing—to talk about head-on. Somehow, talking about a stuffed animal’s meltdown is way easier than admitting, “I’m feeling overwhelmed.”

Experience:

During one of our Peace of Mind lessons (thank you, Diesener, 2017), we were exploring different scenarios and practicing how we might feel in each one—and what we could do about those feelings. It was one of those magical moments when the kids were actually listening, and no one was licking the carpet.

I asked,

“What if you go into the bathroom… and you see a spider?”

Without missing a beat, one child threw both hands in the air and shouted,

“Aaaaaarrrgghh! I feel scared!”

—complete with wide eyes and dramatic shiver. Oscar-worthy, really.

So I asked,

“It’s okay to feel scared—but why do you think you’re scared of spiders?”

They looked up and said,

“Because they’re so creepy… and my mom always screams when she sees one.”

Ah, there it is—emotional modeling in action.

I gently asked,

“What do you think would help you feel better when you feel scared?”

They thought for a second.

“A hug.”

“Would you like a hug right now?”

“Yes.”

So we shared a sweet little hug—a small moment, but one packed with emotional insight.

Then I added,

“If I saw a spider, I’d gently pick it up and take it outside. I like spiders.”

They looked at me, jaw slightly dropped, and said in awe,

“That is brave.”

And just like that, we had covered fear, empathy, emotional regulation, and bravery—plus a bit of spider diplomacy—all in one tiny teaching moment. This simple role-play scenario gave the child a chance to pause, explore the feeling, and “live through it” in a safe and supported way. It also opened the door to a valuable lesson: people can feel very differently in the same situation—and that’s okay. In this particular story, the fear of spiders was clearly passed down from a parent. And that’s often the case—many emotional responses are modeled by adults, even unintentionally. The tricky part is that children sometimes adopt these feelings without fully understanding them. So they’re not just reacting to a spider—they’re reacting to someone else’s fear of the spider. By unpacking these moments in play, children can begin to untangle what they truly feel from what they’ve picked up from others.

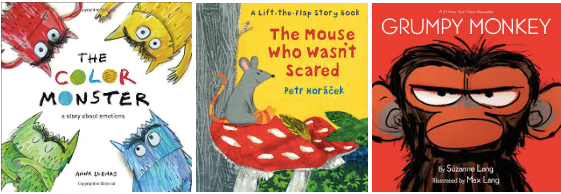

Incorporating books that discuss emotions

Incorporating books about emotions into your day is a powerful (and cozy) way to support children’s emotional literacy—one of the cornerstones of social-emotional learning. Through stories, children can begin to recognize, name, and better understand their own feelings, as well as those of others. These books create a safe space to explore complex emotions and offer up the vocabulary kids need to talk about them. Plus, there’s something magical about watching a child light up when they see themselves in a character’s emotional journey—whether it’s a grumpy bear, a nervous bunny, or a dragon learning to stay calm. With so many thoughtfully written emotion-themed books out there, it’s easy to dive deeper into specific feelings and help children process them one story at a time (bonus points if there’s a cuddly read-aloud voice involved).

Experience:

It was story time, and I pulled out a favorite: How Full is Your Bucket?—a lovely book all about how our actions can either fill someone’s emotional bucket or, unfortunately, dip into it. We read, we talked, and (as always) my little audience had thoughts. So many thoughts.

They asked questions about the feelings in the book:

“Why was Anna sad?”

“What does it mean to ‘dip’ a bucket?”

“Can you fill your own bucket with cookies?”

The conversation was rich and meaningful—even if a few kids were mostly in it for the cookie theory.

Fast forward to the next day. One child approached me with a furrowed brow and said very seriously,

“Someone dipped into my bucket and now I feel angry… like Anna did in the book.”

Instant goosebumps.

Turns out, another child had said they didn’t want to play with them—pretty much the exact situation from the story. But instead of crying or lashing out, this child named the feeling, made the connection, and used the language from the book. We were in full emotional-literacy-in-action mode.

So we sat together and talked it through. I gently explained how it’s okay to feel sad or disappointed, and that just like in the story, we all have the choice to play with different people—or sometimes, just with ourselves. No one was wrong. No one was mean. It was just a moment of figuring out feelings, boundaries, and friendship—preschool style.

But that moment? That moment was a win.

A little story, a little heartache, and a very full bucket of emotional growth.

Model different emotions in situations and explain

Modeling emotions for children isn’t just helpful—it’s one of the most powerful tools we have. When adults openly express and talk through their feelings, children learn to do the same. It teaches them how to recognize, understand, and manage their own emotions, and builds critical skills like empathy, emotional vocabulary, and self-regulation—all of which support strong relationships and resilience (Tominey et al., n.d.). By witnessing adults navigate challenging emotions—say, a parent calmly explaining, “I’m feeling really frustrated right now, so I’m going to take a deep breath”—children are shown, in real time, what healthy emotional coping looks like (Miller, n.d.). It turns what could be a tricky moment into a teachable one. And honestly, nothing builds emotional intelligence faster than a good role model (yes, even on your worst hair day).

Experience:

During one of our Peace of Mind gatherings (we were reading How Big Are Your Feelings? by Diesener, 2017), we were talking about how emotions can come in different sizes—tiny like a tickle or big like a storm. The children were seated in a cozy circle, and I decided it was time for a little dramatic flair.

So right in the middle of our calm little group, I threw myself on the floor—full-on meltdown mode. I started kicking, screaming, crying, and even stomping like a frustrated cartoon character. The children froze for a split second with wide, curious eyes—probably wondering if I’d lost my marbles or just dropped one too many clipboards.

Then something amazing happened.

Instead of laughing or shrinking away, they jumped right into action. One by one, they began offering the calming strategies we’ve practiced so often:

“Do mountain breaths!”

“Get some water!”

“Ask someone for a hug!”

So, still “crying” (with just a touch of dramatic flair), I slowly raised my hand and started doing mountain breaths. Then I took a sip of water from my nearby cup. Still sniffling, I walked over to a fellow educator and asked, “Can I have a hug?” (She gave me a good one.)

Feeling calmer, I quietly returned to the circle, found my spot, and looked around at the group of mini mindfulness coaches.

Me: “What feeling do you think I had? And how big was it?”

Children: “Angry!” “Frustrated!” “Sad!” “Mad!”

Me: “You’re all right—I was feeling a LOT of things at once, and I didn’t know what to do for a second. But I listened to your amazing ideas. Can you remind me again what you suggested?”

Child 1: “You did your mountain breaths.”

Child 2: “You drank some water.”

Child 3: “You asked for a hug.”

Me: “And why do you think I did those things?”

Child 1: “Because it helps you calm your body.”

And there it was—a moment that showed just how powerful our emotional learning has become. They didn’t just remember the techniques—they applied them. Not to themselves this time, but to someone else. And that’s not just labeling emotions. That’s compassion in action. Sometimes, children need to see that we adults have big feelings too—that we don’t always have it all together (shocking, I know). Those moments, as imperfect as they may feel, are actually golden teaching opportunities.

All children are different—and that’s exactly why a one-size-fits-all approach just doesn’t work when it comes to emotional development. Some children may pick up on feelings and labels quickly, while others need a little more time, more support, or a completely different approach (just like we adults do!). The important thing is that we meet them where they are. There’s strong evidence in the research showing that focusing on emotional and social competence brings wide-ranging benefits—everything from improved behavior and academic success to better mental health, social inclusion, and overall wellbeing (Weare & Gray, 2003). But at the core of it all is one powerful message we must keep repeating: It is okay to feel. Whatever emotion a child is facing—joy, anger, worry, or sadness—they need to know it’s valid. And as the adults in their world, it’s up to us to keep growing too—reflecting on our own emotional habits and asking ourselves how we can best support the little hearts in front of us. It’s not always easy, but little by little, with care and intention, we can make a big difference. A difference that helps raise emotionally healthy, happy children—one feeling at a time

Until next time—may your ‘happy’ stay joyful, your ‘frustrated’ stay manageable, and your preschoolers never confuse ‘excited’ with ‘time to run screaming across the room.’ See you behind the crayons!

-The Teacher Behind the Crayons

💬 I’d love to hear from you! Have you had a “pause and breathe” moment with your little learners? Or maybe a funny story about a fire drill and a glitter explosion? Share your thoughts, questions, or classroom wins in the comments below—let’s keep the conversation going.

References

Diesener, J. (2017). Peace of Mind Core Curriculum for Early Childhood: A Mindfulness-based Social and Emotional Learning Program Designed to Help Young Children Self-regulate, Strengthen Social Skills, and Increase Self-esteem. Peace of Mind Incorporated.

Goleman, D. (2005). Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ. Random House Publishing Group.

Miller, C. (n.d.). How to Help Children Calm Down. Child Mind Institute. Retrieved May 18, 2025, from https://childmind.org/article/how-to-help-children-calm-down/

Neff, M. A. (n.d.). The Feelings Wheel: Learn How to Identify Your Emotions. Neurodivergent Insights. Retrieved May 18, 2025, from https://neurodivergentinsights.com/the-feelings-wheel/

Sutton, J., & Millacci, T. S. (2021, November 24). What is Emotional Awareness? 6 Worksheets To Develop EI. Positive Psychology. Retrieved May 18, 2025, from https://positivepsychology.com/emotional-awareness/

Tominey, S. L., O’Bryon, E. C., Rivers, S. E., & Shapses, S. (n.d.). March 2017 – Teaching Emotional Intelligence in Early Childhood. NAEYC. Retrieved May 18, 2025, from https://www.naeyc.org/resources/pubs/yc/mar2017/teaching-emotional-intelligence

Weare, K., & Gray, G. (2003). What Works in Developing Children’s Emotional and Social Competence and Wellbeing? DfES Publications.

Discover more from Behind The Crayons

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Teacher Behind The Crayons

You May Also Like

Emotional Intelligence: Teaching children about Motivation

June 23, 2025

Emotional Intelligence: Teaching children about Self- Awareness

June 20, 2025