Emotional Intelligence: Teaching children about Empathy

After exploring motivation in the last post and how it helps children develop an internal drive to learn, connect, and grow, we now turn to another essential piece of the emotional intelligence puzzle: empathy.

Empathy might seem like one big, fuzzy feeling—but it’s actually made up of several smaller, important parts working together behind the scenes. Breaking it down into specific subcomponents helps us understand how empathy grows and shows up in early childhood (hint: it’s not always hugs and “I’m sorry”s). These include emotional recognition, affective empathy, cognitive empathy, empathic concern, and self–other awareness. Each one adds a little more depth to how children connect with others—and explains why sometimes they’ll offer a toy to a crying friend… and other times they just keep playing like nothing ever happened.

Emotional Recognition

Emotional recognition is the skill that helps children read the room—or at least start to notice when a friend is smiling, frowning, or gearing up for a good stomp. It’s the ability to identify and label emotions in others by tuning into facial expressions, body language, and tone of voice. For preschoolers, this skill is the first stepping stone to developing empathy. After all, before a child can respond kindly to a friend who’s upset, they first need to notice that the friend is upset in the first place. Emotional recognition helps children make sense of social situations, communicate more clearly, and begin to understand that other people have feelings too (Denham et al., 2003; Saarni, 1999). And yes—it’s also what eventually helps them realize that the teacher’s “I’m fine” face might not mean everything’s actually fine.

Here are some simple activities to help to achieve the goal of fostering children to be able to identify and label emotions in others:

- Emotion Flashcards: Show pictures of facial expressions and ask children to name the emotion.

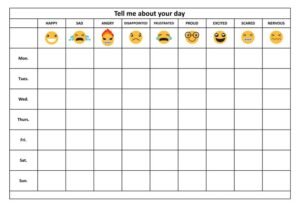

- Feelings Check-In: Use a daily chart where children place their name/photo under an emotion (happy, sad, angry, etc.) as they arrive.

- Storybook Discussions: While reading books, pause to ask, “How do you think this character feels right now? How do you know?”

- Mirror Play: Have children mimic facial expressions and guess each other’s emotions.

Experience:

One of my favorite tools for helping children recognize emotions is something wonderfully simple: a mirror.

One morning, I set up a little emotional exploration station with a child-sized mirror, a basket of emotion cards, and a few prompts like “Can you make a happy face?” or “What does your sad face look like?” A few children gathered, giggling as they stretched their faces into silly shapes. But it was Ava who caught my attention.

Ava was usually pretty quiet during group discussions about feelings. She’d listen closely, but rarely shared, often unsure of the words to describe how she felt. But when she sat in front of the mirror, something changed. She picked up a card with a cartoon face that looked angry—eyebrows slanted, lips tight—and held it up beside her own reflection.

“I can do that one,” she said. She scrunched up her face, furrowed her brows, and looked at herself seriously. Then she said, “That’s my mad face. I do that when someone takes my stuff.”

I crouched beside her and nodded. “Wow, you really noticed that. Do you feel it anywhere else in your body when you’re mad?”

“My cheeks get hot,” she said, without hesitation.

That moment of mirror play turned into a breakthrough. Ava wasn’t just playing—she was connecting. She was beginning to identify her emotions by what they looked and felt like, giving her the language (and the confidence) to name them when they showed up later.

From then on, Ava became more vocal during our feelings check-ins. She didn’t always use big words—but she noticed, and she shared. And it all started with a mirror, a little curiosity, and the freedom to explore her face like a story waiting to be told.

Affective Empathy (Emotional Contagion)

Affective empathy is that heart-squish moment when a child sees a friend crying and suddenly looks like they might burst into tears too. It’s the instinctive, emotional response kids feel when they pick up on someone else’s feelings—like getting sad because someone else is sad, or giggling just because everyone else is. This kind of empathy tends to show up early in development, and it’s a sign that children are emotionally in tune with the people around them. In preschoolers, affective empathy lays the groundwork for those first real friendships and warm, meaningful connections (Zahn-Waxler & Radke-Yarrow, 1990; Hoffman, 2000). Our goal in nurturing this isn’t to create tiny emotional sponges, but rather to help children strengthen their ability to tune in and care—one “Are you okay?” at a time.

Some suggestions to foster the development of affective empathy:

- Emotion Puppets or Dolls: Use puppets to act out scenarios (e.g., puppet is crying), then invite children to comfort them.

- Shared Emotional Experiences: Watch short age-appropriate videos or animations and discuss how it made them feel.

- Emotion Matching Games: Match situations with the emotion they might cause (e.g., losing a toy = sad).

- Group Reflection Time: After an emotional event (e.g., someone got hurt), gather the group to reflect on how it felt and how everyone responded.

Experience:

It happened, as these things often do, in the middle of the busiest part of the day—clean-up time. Blocks were being tossed (not stacked), chairs were being bumped, and somewhere in the chaos, Liam tripped over a toy and fell hard. There was a loud thud, a short pause, and then the unmistakable sound of hurt and heartache—tears.

I helped Liam to the cozy corner, checked him over, offered comfort, and gave him space to settle. But what struck me most was the look on the other children’s faces—wide eyes, worried glances, and that quiet, unsure energy that often comes after someone gets hurt.

After Liam was calm and ready, I gathered the group together for a reflection circle—something we do when emotions run high, not just for the child involved, but for everyone.

I asked, “How did it feel when Liam got hurt?”

There was a pause, and then Ava said softly, “It made my tummy feel tight.”

Another child added, “ It was loud and I felt scared.”

That’s when I could see the shift. The empathy wasn’t just about recognizing that Liam was hurt—it was about feeling that hurt too, in their own little bodies. It was affective empathy in action. These weren’t just observers—they were emotionally with him.

We talked about what helped: who brought the tissue, who stayed close, who said “Are you okay?” Even small gestures had big meaning.

That group reflection gave space not just for Liam to feel supported, but for the others to process their own reactions—and recognize that emotions don’t happen in isolation. They ripple. And with the right guidance, those ripples turn into connection.

Cognitive Empathy

Cognitive empathy is when a child starts to think about how someone else might be feeling—even if it’s different from how they feel. It’s that mental leap of, “Hmm, maybe she’s sad because she didn’t get a turn,” instead of, “I’m fine, so everything must be fine.” In preschoolers, this ability starts blooming as they develop what we call theory of mind—that wonderful (and sometimes wobbly) realization that other people have their own thoughts, feelings, and perspectives (Wellman, 1990; Eisenberg et al., 2006). Cognitive empathy is what helps children work through conflicts, play cooperatively, and start building those deeper, more thoughtful relationships with peers. And while it doesn’t mean they’ll suddenly become conflict resolution experts overnight, it does mean they’re on the right track.

Try some of the simple activities below to help children grow this skill—and maybe prevent a few “I thought it was mine!” meltdowns along the way.

- Role Play: Set up pretend play scenarios like a doctor visit, birthday party, or playground conflict to explore different perspectives.

- “Walk in Their Shoes” Game: Have children imagine how someone else might feel in a given situation (“What if you were left out of the game?”).

- Guess the Feeling: Describe a situation without showing emotion, and have children guess how the person might feel.

- Perspective-Prompting Questions: During play or storytelling, ask, “What do you think she wants?” or “Why did he do that?”

Experience:

It started with a simple game during morning circle—“Guess the Feeling.” I told a short story, keeping my face and voice neutral:

“Yesterday at the park, Mia asked to play with two friends, but they didn’t say anything and kept playing without her. Then she sat on a bench by herself.”

The room was quiet. I looked around and asked, “How do you think Mia felt?”

Hands shot up immediately:

“Sad!”

“Lonely!”

“Left out,” one child said quietly.

Then I asked the golden follow-up: “Why?”

Harper, who was usually more focused on what’s fair than what’s felt, chimed in. “Because they didn’t answer her. And if they didn’t say anything, maybe she thought they didn’t want her there.”

That was it—cognitive empathy at work. Harper wasn’t just naming a feeling; she was imagining what Mia was thinking and experiencing, even though she wasn’t in that situation herself.

We kept going with a few more scenarios, and the responses got deeper—less about just labeling emotions, and more about thinking through why someone might feel that way.

Later that day during outdoor play, I noticed Harper sitting beside another child on the bench. “Are you okay?” she asked. “You’re quiet… is it like Mia in the story?”

It was one of those small moments that made my teacher heart do a little somersault. Because while kindness is wonderful, understanding is what helps children reach beyond their own perspective—and that’s where real connection begins.

Empathic Concern (Compassionate Response)

Empathic concern is when empathy puts on its superhero cape. It goes beyond simply understanding how someone feels—it’s about wanting to do something to help. In preschoolers, this might look like offering a teddy bear to a crying friend, rubbing someone’s back (usually a bit too enthusiastically), or saying, “It’s okay” in that sweet, wobbly voice only they can manage. These small, compassionate actions are powerful building blocks for kindness, moral development, and a sense of community in the classroom (Eisenberg & Fabes, 1998; Kochanska et al., 2002). It’s empathy in action—turning “I feel bad for them” into “What can I do to help?”

Try these simple ideas below to help encourage caring behaviours and support children in acting on those big, empathetic feelings—without needing a cape:

- Kindness Jar: Add a pompom each time a child helps a friend; when full, celebrate with a class activity.

- “What Can We Do?” Circle: When someone is upset, gather the group to brainstorm ways to help them feel better.

- Helping Jobs: Assign daily “kindness jobs” like helping a friend clean up or checking on someone who’s sad.

- Empathy Stories: Share real or fictional stories where someone helps another person, and discuss what made it kind.

Experience:

Our Kindness Jar sat on the shelf like a little beacon of hope—with soft, fluffy pompoms just waiting to be earned through helpful hands and kind hearts. The children knew the deal: every time someone showed kindness or helped a friend without being asked, a pompom got dropped in the jar. When it was full, we’d vote on a class celebration. (Spoiler alert: popcorn and a pajama party wins every time.)

One rainy afternoon, as everyone was packing up from painting, a loud crash came from the art table. Liam’s tray of watercolors had hit the floor, and with it, half of his carefully made rainbow.

His face fell. He didn’t cry—but he looked devastated.

Before I could even step in, Harper (who had just finished cleaning her own brushes) walked over, crouched down, and said, “I’ll help you clean it up.” No sighing. No grown-up prompting. Just a quiet, natural offer of support.

Liam looked at her, surprised. “Really?”

“Yeah,” she said, already wiping the spilled paint. “We can make another one tomorrow.”

I reached over, picked up a pompom, and walked it over to the jar. Plunk. The whole class paused to look.

“What did Harper do?” I asked.

“She helped Liam when he was sad,” someone said.

“She didn’t even wait to be asked,” another added.

We celebrated the moment—not just with the pompom, but with a short circle time reflection on what kindness feels like. Liam smiled for the first time that afternoon. Harper beamed. And the jar inched one pompom closer to pajama day.

Moments like that remind me: compassionate responses don’t have to be loud or elaborate. They just need to be real—and when they are, they ripple.

Self-Other Awareness

Self–other awareness is like the “you are you, and I am me” lightbulb moment. It’s when children begin to understand that their feelings and experiences are their own—and that other people might feel differently, even in the same situation. For preschoolers, this awareness is essential for managing their own emotions without absorbing everyone else’s. It helps them respond with empathy without getting swept up in someone else’s emotional rollercoaster (because let’s face it—there are already plenty of ups and downs in a preschool day). This skill lays the groundwork for emotional boundaries and the kind of balanced empathy that allows children to care for others while still feeling secure in themselves (Thompson, 2006; Brownell et al., 2013).

Help children begin to recognize their own emotions—and understand how those might be different from what others are feeling—with the following simple and supportive ideas:

- My Feelings vs. Your Feelings Game: Show two characters with different emotions and ask children to say how they feel vs. how each character feels.

- Emotion Journals (Drawing Version): Have children draw a picture of how they felt during different parts of the day.

- Breathing or Body Awareness Exercises: Teach children to notice their own emotional and physical state (e.g., “What does your body feel like when you’re mad?”).

- Reflection Time: After a conflict or strong emotion, guide children in talking about their own feelings vs. how others might have felt.

Experience:

The sparkly blue scissors strike again.

It was one of those classic preschool conflicts—Ethan and Mateo both reached for them at the same time. There was a quick tug, a frustrated shout, and then Mateo in tears while Ethan stood nearby, arms folded, clearly still riding the wave of his own frustration.

Rather than jumping straight into “fix it” mode, I invited Ethan to our cozy reflection corner—a calm little nook with pillows, picture books, and space to think. Once we sat down, I said gently, “Let’s figure out what happened together.”

Ethan looked down at his hands. I began with the simple stuff:

“What were you feeling when you grabbed the scissors?”

He answered quickly. “Mad. I waited forever.”

“Totally fair,” I nodded. “And what do you think Mateo was feeling when that happened?”

He paused. Thought about it. “Sad, maybe. Or surprised.”

“Do you think his feelings were the same as yours?”

He shook his head. “No… I was mad, but he didn’t even know I was waiting.”

And just like that—we landed on a powerful moment of self-other awareness. Ethan began to understand that while he felt frustrated, Mateo’s experience was completely different—and that both feelings could exist at the same time. His intention wasn’t to hurt; it was to be seen. But he began to see that his actions had landed differently on someone else.

We talked a bit more—about using words, about asking for a turn, and about what we can do when big feelings take over. Then Ethan stood up, walked over to Mateo, and said, “Sorry I pulled. I just really wanted a turn.” Mateo gave a tiny nod and wiped his eyes.

It wasn’t dramatic. It wasn’t perfect. But it was real. And in that moment, Ethan took a small but mighty step toward recognizing that his world isn’t the only one that exists—and that understanding how someone else feels doesn’t take away from his own emotions. It just helps him move through them with kindness.

As a preschool teacher, I get a front-row seat to the everyday magic (and occasional mayhem) of emotional development—and let me tell you, empathy is everything. It’s at the heart of building friendships, solving playground squabbles, and learning how to say, “I’m sorry,” without being told to. By nurturing each subcomponent—emotional recognition, affective empathy, cognitive empathy, empathic concern, and self-other awareness—we’re not just helping children be “nice.” We’re teaching them how to truly connect, manage their big feelings, and be caring, thoughtful members of their little communities. These aren’t fluffy extras—they’re essential skills that fuel cooperation, conflict resolution, and all-around compassionate behavior. With intentional teaching, playful activities, and a healthy dose of adult modeling (yes, even when we’d rather sigh deeply into our coffee mugs), we can help lay the foundation for emotional intelligence that children will carry with them long after they’ve left the block corner behind.

Up next, we’ll dive into the final component in our emotional intelligence series: Social Skills—what they look like in preschoolers, why they matter so much, and how we can nurture them through everyday moments, playful connection, and a little bit of modelling magic.

Here’s to big hearts in small bodies, learning to care, connect, and sometimes share the good scissors. Catch you soon—behind the crayons.

— The Teacher Behind the Crayons

💬 I’d love to hear from you! Have you had a “pause and breathe” moment with your little learners? Or maybe a funny story about a fire drill and a glitter explosion? Share your thoughts, questions, or classroom wins in the comments below—let’s keep the conversation going.

References

Brownell, C. A., Svetlova, M., & Nichols, S. R. (2013). To share or not to share: When do toddlers respond to another’s needs? Infancy, 18(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7078.2011.00086.x

Denham, S. A., Blair, K. A., DeMulder, E., Levitas, J., Sawyer, K., Auerbach–Major, S., & Queenan, P. (2003). Preschool emotional competence: Pathway to social competence? Child Development, 74(1), 238–256. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00533

Eisenberg, N., & Fabes, R. A. (1998). Prosocial development. In W. Damon (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional, and personality development (5th ed., pp. 701–778). Wiley.

Eisenberg, N., Spinrad, T. L., & Morris, A. S. (2006). Empathy-related responding in children. In M. Killen & J. G. Smetana (Eds.), Handbook of moral development (pp. 517–549). Psychology Press.

Hoffman, M. L. (2000). Empathy and moral development: Implications for caring and justice. Cambridge University Press.

Kochanska, G., Barry, R. A., Stellern, S. A., & O’Bleness, J. J. (2002). Early development of conscience: A longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 38(3), 263–275. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.38.3.263

Saarni, C. (1999). The development of emotional competence. Guilford Press.

Thompson, R. A. (2006). The development of the person: Social understanding, relationships, conscience, self. In N. Eisenberg (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional, and personality development (6th ed., pp. 24–98). Wiley.

Wellman, H. M. (1990). The child’s theory of mind. MIT Press.

Zahn-Waxler, C., & Radke-Yarrow, M. (1990). The origins of empathic concern. Motivation and Emotion, 14(2), 107–130. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00991639

Discover more from Behind The Crayons

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

You May Also Like

Emotional Intelligence: Teaching children about Motivation

June 23, 2025

👀 I See You – A Story About Slowing Down and Looking Closer

June 25, 2025