Emotional Intelligence: Teaching children about Self- Awareness

Self-awareness is all about helping young children begin to notice what’s going on inside themselves—what they’re feeling, thinking, and doing. In preschool, this might look like a child saying, “I’m sad,” or realizing they need a break when they’re frustrated. It’s the first step in understanding how their actions affect others and how to make thoughtful choices. When we support self-awareness in early childhood, we’re giving kids the tools to manage their emotions, build stronger relationships, and feel more confident in who they are (Morin & Cunningham, n.d.).

A child who’s still developing self-awareness might have a tough time understanding their own emotions, behaviors, and how those things ripple out to affect others. This can show up as trouble identifying feelings (“I’m not mad!”—as they throw a crayon), not quite grasping the consequences of their actions, or struggling to recognize their own strengths and areas for growth. Sometimes, it even means not really knowing what matters to them yet or how to connect the dots between their experiences. But here’s the good news: self-awareness isn’t something kids are expected to have all figured out—it’s something they build, one little lightbulb moment at a time.

As a preschool teacher, I want to zoom in on three key areas: cognitive, physical, and external self-awareness, and explore how we can support our little ones as they grow into the best versions of themselves—preferably without stepping on too many Lego bricks along the way.

Each of these areas include the broad definition with added activities/actions to support it as well as personal experience stories.

Cognitive self-awareness

Cognitive self-awareness is all about how children start to think about their own thoughts, feelings, and preferences—kind of like the tiny beginnings of an inner voice. It’s the foundation for things like understanding, “I’m better at puzzles than at drawing,” or, “I feel nervous when it’s my turn to talk.” In preschoolers, this doesn’t look like deep journaling sessions (obviously), but rather simple moments where they reflect on what they like, what they’re feeling, or what they’re learning.

By the end of the preschool years, most children have developed a budding sense of self. They can recognize themselves in photos and mirrors (sometimes proudly shouting, “That’s me!” even when covered in spaghetti), and they start to understand that they are their own person—separate from others—with their own actions, feelings, and motivations. Alongside this, they begin to grasp that other people have their own thoughts and beliefs too, which is part of what we call theory of mind—a fancy term for realizing the world doesn’t revolve entirely around them (a tough pill for some preschoolers to swallow!). At this stage, children also begin to form self-esteem, shaped by their accomplishments and the feedback they receive from the grown-ups around them. They become more tuned in to how they compare with others, which can spark feelings like pride… or, occasionally, the dramatic flop of preschool shame (Malikovna, 2024).

You can support it by:

Celebrating self-discovery: “You noticed you’re really good at building towers—great thinking!”

Encouraging children to make choices and explain the them: “Why did you pick the red marker?”

Using open-ended reflection questions: “How did that make you feel?” or “What would you do next time?”

Some simple and engaging activities can also help children understand how they think, learn, and problem-solve. You can find few suggestions below:

What’s in my brain?

Goal: Help kids reflect on their thoughts.

How it works: Give children a head-shaped outline and ask them to draw or color what’s “in their brain” today—what they’re thinking about, remembering, wondering, or feeling.

Say something like: “Let’s draw what’s going on in our brains! Are you thinking about lunch? About your toy at home? Let’s put those thoughts on paper!”

How did I solve that?

How it works: After a puzzle, matching game, or building activity, ask simple reflection questions:

- “What did you do when the pieces didn’t fit?”

- “What helped you figure it out?”

- “What could you try next time?”

Tip: Keep it short and sweet. Even a one-sentence answer helps them reflect.

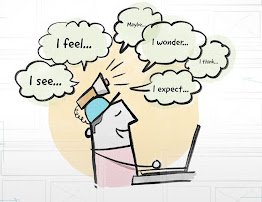

“Think Aloud” Model

Goal: Teach kids it’s OK (and helpful) to talk through their thinking.

How it works: Narrate your own thought process during tasks:

“I’m trying to build this tower… Hmm, that block is wobbly. I think I need a bigger one on the bottom!”

Kids learn: Thinking is something we do, and it can be shared and explored out loud.

Storytime with Thinking Questions

Goal: Develop metacognition through stories.

How it works: During read-alouds, pause and ask:

- “What do you think the character is thinking?”

- “Why did they make that choice?”

- “What would you do?”

This helps children notice thoughts, motivations, and decision-making—first in characters, then in themselves.

Experience:

During morning free play, the room was buzzing—blocks clattering, crayons rolling, dramatic play in full swing. Right in the middle of it all, Lily was sitting at the art table with a glue stick, a few scraps of paper, and the most peaceful expression on her face.

Later, during our reflection circle, I asked the group, “What did you like doing today?”

Lily raised her hand quietly and said, “I liked the quiet table. When it’s loud, I feel all jumpy inside. But when it’s quiet, my brain feels happy.”

It was such a simple statement, but it stopped me in my tracks. She wasn’t just naming a preference—she was tuning into her internal experience and making a connection between how she feels and what she needs. That’s cognitive self-awareness at its best.

I smiled and said, “That’s really helpful to know about yourself, Lily. You found what helps your brain feel calm—and that’s something even grown-ups are still learning.”

That day, we added a little “quiet corner” sign to the art table, and soon a few other children began choosing it when they felt overwhelmed too. One small moment of self-discovery rippled into a shift in how our whole class understood themselves—and each other.

Physical self-awareness:

This type of self-awareness is all about the body: understanding where it is in space, what it can do, and how it feels. Think of it as the difference between a child who knows they’re about to bump into someone… and one who barrels through the block area like a tiny bulldozer. Physical self-awareness helps children move with purpose, respect personal space, and even begin to connect physical sensations with emotions.

Helping young children become more aware of their bodies and feelings does more than just build coordination—it lays the foundation for lifelong skills. Here’s how:

- Stronger social-emotional skills: When kids understand what they’re feeling and how their body reacts, they’re better equipped to manage emotions and connect with others.

- Higher self-esteem: Recognizing their own strengths—like being fast runners, great hoppers, or good at calming themselves down—can make them feel more confident and capable.

- Better self-regulation: When children can tune into their physical and emotional needs, they learn how to pause, adjust, and respond instead of react—an essential skill for school and life.

Here are some ways to encourage children to understand and connect with their own physical body by providing opportunities for movement, using mirrors, talking about feelings and using flashcards:

“Move Like Me!” Movement Exploration Game

Goal: Provide opportunities for free movement and body awareness.

How it works: Create a safe, open space (indoors or outdoors). Start by demonstrating a simple movement (e.g., jump like a frog, tiptoe like a cat, stretch like a tall tree). Then invite the children to take turns being the leader and choosing a movement for everyone to copy.

You can say: “Let’s explore how our bodies move! Can you show us a way to move across the room? What does your body want to do right now?”

Optional extension: Add music, props like scarves or ribbons, or themed prompts like “move like the weather” or “move like your favorite animal.”

Why it works:

- It encourages physical self-awareness

- Builds confidence as children lead the group

- Supports gross motor development and imaginative play

“Mirror Me!” Body Awareness Game

Goal: Help children visually recognize their own body and movements using mirrors.

How it works:

Place a full-length mirror at child level in your classroom or movement area. Invite children to stand in front of the mirror and try simple movements while watching themselves.

Try prompts like:

- “Can you make a big shape with your arms?”

- “What happens when you jump?”

- “Can you wave with one hand and watch it move?”

- “Make a silly face—can you copy it again?”

Variation – Partner Version

Children pair up (at school) or family members join in. One person is the “mirror,” copying the slow movements of their partner, who leads. Then they switch roles.

Why it works:

- Encourages physical self-awareness by connecting visual input with body movement

- Promotes focus, balance, and coordination

- Builds vocabulary (“bend,” “stretch,” “turn,” “wave”)

- Supports social skills in the partner version

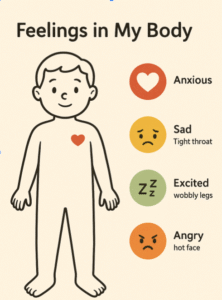

“Feelings in My Body” Check-In

Goal: Help children link physical sensations to emotions.

How it works: Show a simple outline of a body (you can draw it or use a printable). Use magnets, stickers, or crayons to mark where children “feel” something in their body when they have certain emotions.

Prompt with gentle questions like:

- “When you feel mad, does your face get hot?”

- “Do you get a wiggly feeling in your legs when you’re excited?”

- “What does your body feel like when you’re sad or worried?”

You can say: “Sometimes our body tells us how we feel—even before our words do! Let’s listen to what it’s saying.”

Optional tools:

- Use a mirror so children can observe their faces or body language.

- Use puppets or stuffed animals to act out feelings first.

Have a chart that shows simple visuals: 💓 fast heart = nervous, 😮 tight shoulders = scared, etc.

Why it works:

- Builds emotional literacy

- Encourages self-awareness and self-regulation

- Helps children recognize early signs of stress or strong emotions

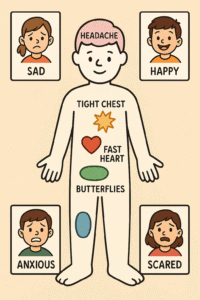

Face & Feel” Flashcard Game

Goal: Help children identify and name emotions, and connect them to how their body feels.

How it works: Use emotion flashcards showing clear, expressive faces (happy, sad, angry, scared, excited, etc.). Sit in a small group or during circle time and hold up one card at a time.

Ask children to:

- Name the feeling : “What do you think this person is feeling?”

- Act out the feeling with their face and body: “Can you show me your angry face?”

- Talk about body sensations: “When you feel angry, what happens in your body? Does your face feel hot? Do your fists clench?”

Add movement or props: Let them “shake out” their feelings with scarves or stretch poses—this supports emotional release and regulation.

Experience:

It was a slow, rainy morning, and I could feel the fidgety energy brewing in the room before the day had even properly started. During our morning meeting, I introduced a new activity: the “Feelings in My Body” Check-In.

I rolled out a big poster of a simple body outline and explained, “Sometimes, our body gives us clues about how we feel—even before we know what to say. Let’s see if we can figure out what our bodies are telling us.”

We talked through some examples, with the help of our classroom puppet, Sunny. “When Sunny’s mad, his cheeks get really warm.” I asked the children, “Where do you feel it when you’re mad?”

Hands shot up. “In my tummy!” “My hands feel like fists!” “I stomp!”

Then it was Sam’s turn. He was usually one of the quieter kids—observant, but not quick to speak up. He slowly walked over to the chart, picked up a magnet, and placed it on the shoulders.

“When I’m scared,” he said softly, “my shoulders feel like a rock.”

The room went quiet in the most beautiful way. You could feel the empathy settle in.

“That’s such a smart thing to notice,” I said. “Your body is telling you something important. What do you think helps your shoulders feel softer again?”

Sam thought for a moment. “When I sit down and hug my bear.”

We added that to his personal calm-down plan.

That small moment wasn’t just about body parts or magnets—it was a powerful act of physical self-awareness. Sam recognized how fear showed up in his body and what helped him feel better. And perhaps most importantly, he felt safe enough to share it with the group.

External self-awareness

This is when children begin to understand that others see them too. It’s the early spark of perspective-taking: “Oh, when I scream, it affects people around me.” Preschoolers developing external self-awareness start to notice how their actions influence their environment and their relationships. It’s the moment when a child pauses after snatching a toy and realizes their friend looks upset—that’s gold! (Legrain et al. 2011).

You can encourage it by:

- Narrating social scenarios: “Look, Maya looks sad—she was playing with that doll.”

- Offering praise when they show awareness: “You saw he was waiting and gave him a turn—what a kind friend you are!”

Below is some activities you can also introduce in order to support the development of external self-awareness.

“What Do You See?” Partner Drawing

How it works: Children pair up with each other or adults. One person describes a simple shape or picture without showing it; the other draws what they hear. Then they compare drawings.

Teaches:

- How others interpret your words/actions

- Perspective-taking

- Communication skills

Photo Feelings

How it works: Take photos of children acting out emotions (happy, sad, tired, proud, etc.). Later, look at the photos together and ask:

- “What do you see on this face?”

- “What might this person be feeling?”

Teaches:

- Reading social cues

- Recognizing how they look to others

‘Kind or Unkind?’ Story Sort

How it works: Read short stories or scenarios (e.g., “She shared her toy,” “He pushed his friend”) and ask:

- “Was that kind or unkind?”

- “How might that make someone feel?”

You can print or draw different pictures related to the stories. Then sort cards into two piles (Kind / Unkind).

Teaches:

- Understanding actions from another’s perspective

- Building empathy and self-reflection

“Walk in Their Shoes” Role-Play

How it works: Use dress-up clothes or puppets and invite kids to act out how someone else might feel in a situation (e.g., being left out, getting help, having a turn taken).

Teaches:

- Empathy

- Emotional role-taking

- Social self-awareness

Experience:

It started with a bin of dress-up clothes. I set out a few hats, scarves, and puppets, and invited the children to help me act out some little “stories.”

The first one was simple: One friend is playing with blocks, another wants to join, but the first friend says no. I slipped a hat onto my puppet and asked, “How do you think this puppet feels when they’re told they can’t play?”

Hands went up. Most answers were what I expected—“sad,” “mad,” “grumpy.”

But then Julia stood up and reached for a scarf. “Can I show you?” she asked. She wrapped the scarf around her neck and said, in a quiet, puppet voice, “I wanted to play… but they didn’t let me. So I went to the book corner and pretended I didn’t care. But I did care.”

It was such a powerful moment—Julia wasn’t just naming a feeling; she was stepping into someone else’s shoes and recognizing how that feeling might show up on the outside. That’s external self-awareness: understanding how others see us and how our actions affect the people around us.

Later, another child acted out “getting help” and said, “I think he felt happy…but maybe a little shy too.” We talked about how sometimes our faces say one thing and our hearts say another—and how important it is to look and listen closely.

These small, dramatic moments gave children a chance to reflect on themselves through the lens of others. It helped them see that feelings don’t always come with clear labels—and that our actions, even unintentional ones, can have a ripple effect.

Model different emotions in situations and explain

I think it’s worth pausing to explain why I’m putting such a spotlight on self-awareness in preschoolers. It’s not just a buzzword—it’s a foundation for so many lifelong skills. Even simple, everyday activities can have a huge impact on shaping more positive outcomes for our little ones. We’re talking about benefits like improved emotional regulation (fewer meltdowns, hooray!), stronger self-esteem, better social skills, more thoughtful decision-making, increased empathy, and yes—even improved academic performance. While I’ve shared area-specific strategies above, don’t underestimate the power of everyday moments: encourage open communication, give children space to explore and make mistakes, build in time for reflection, and most importantly—model self-awareness yourself. After all, kids are always watching, and if they see you take a deep breath instead of losing it when the paint water spills again, that’s a lesson in emotional regulation they won’t find in any workbook.

Once children begin to develop self-awareness—recognizing their own emotions, thoughts, and actions—they start building the foundation for another essential emotional intelligence skill: self-regulation. In the next post, we’ll explore what self-regulation looks like in the preschool years and how we can support children as they learn to manage big feelings, navigate social situations, and find their calm when the world around them feels anything but.

Until next time—may your mirrors be clean, your emotions be named, and your preschoolers continue discovering their big feelings without wiping their faces on your shirt.

-The Teacher Behind the Crayons

💬 I’d love to hear from you! Have you had a “pause and breathe” moment with your little learners? Or maybe a funny story about a fire drill and a glitter explosion? Share your thoughts, questions, or classroom wins in the comments below—let’s keep the conversation going.

References

“Teaching Self-Awareness to Preschoolers.” Study.com, 1 September 2016, study.com/academy/lesson/teaching-self-awareness-to-preschoolers.html

Sutton, J., & Millacci, T. S. (2021, November 24). What is Emotional Awareness? 6 Worksheets To Develop EI. Positive Psychology. Retrieved May 18, 2025, from https://positivepsychology.com/emotional-awareness/

Goleman, D. (2005). Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ. Random House Publishing Group.

How children develop self-awareness. (2024, April 3). Busy Brains Activity Packs. Retrieved May 19, 2025, from https://www.busybrainsactivitypacks.co.uk/post/how-children-develop-self-awareness

How To Build Self-awareness For Kids: 10+ Best Practices. (n.d.). La Petite Ecole Ho Chi Minh. Retrieved May 18, 2025, from https://www.lpehochiminh.com/en/self-awareness-for-kids/

How to Teach Self-Awareness Skills to Children. (2021, September 3). Whole Child Counseling. Retrieved May 18, 2025, from https://www.wholechildcounseling.com/post/how-to-teach-self-awareness-skills-to-children

Kaiser, E. (2023, June 6). What is self-awareness and why is it important — Better Kids. Better Kids. Retrieved May 18, 2025, from https://betterkids.education/blog/what-is-self-awareness-and-why-is-it-important

Malikovna, N. G. (2024). Formation of Self-Awareness in Preschoolers. Excellencia International Multi-Disciplinary Journal of Education, 2(6), 2994-9521. Retrieved 05 19, 2025, from file:///Users/Gerda/Downloads/1265-1268+Formation+of+Self-Awareness+in+Preschoolers.pdf

Morin, A., & Cunningham, B. (n.d.). What is self-awareness? Understood.org. Retrieved May 19, 2025, from https://www.understood.org/en/articles/the-importance-of-self-awareness

Rochat, P. (2003, December). Consciousness and Cognition. Five levels of self-awareness as they unfold early in life, 12(4), 717-731. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1053810003000813Legrain, L., et al. “Consciousness and Cognition.” Distinguishing three levels in explicit self-awareness, vol. 20, no. 3, 2011, pp. 578-585. ScienceDirect, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1053810010001984. Accessed 9 June 2025.

Discover more from Behind The Crayons

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

You May Also Like

Emotional Intelligence: Teaching children to Recognize and Label Their Emotions

June 18, 2025

Emotional Intelligence: Teaching Children About Self-Regulation

June 23, 2025

One Comment

backlinks meaning in tamil

woh I enjoy your blog posts, saved to fav! .